by Georgia Mirica

The “Junimea” association adopted the following French motto: « rentre tout le monde, restent ceux qui peuvent » (all may come, but only those who can stay may do so). As identified by philosopher and philologist Tudor Vianu, the defining characteristics of the “Junimea” movement were: the philosophical spirit, the oratorical spirit, the appreciation of irony, the critical spirit, and the appreciation of the classic and the academic. It is important to note that the founding members of the “Junimea” were young intellectuals who had completed their studies abroad, mostly in Germany. As a result, the members of the movement looked up to German philosophers, such as Arthur Schopenhauer, and German literary trends, with Romanticism being one of such influences. It is no coincidence that, at a time when the Romanian Intellectual society was highly receptive to French influences, members of the “Junimea” came to be known as the “Germanophiles”. This does reflect the nature of the association’s political believes, taking into account the fact that, for the majority of the 19th Century, the revolutionary spirit ran rampant in France, while “Junimea” held conservatism as its core belief, and, therefore, dismissed excessive French influence.

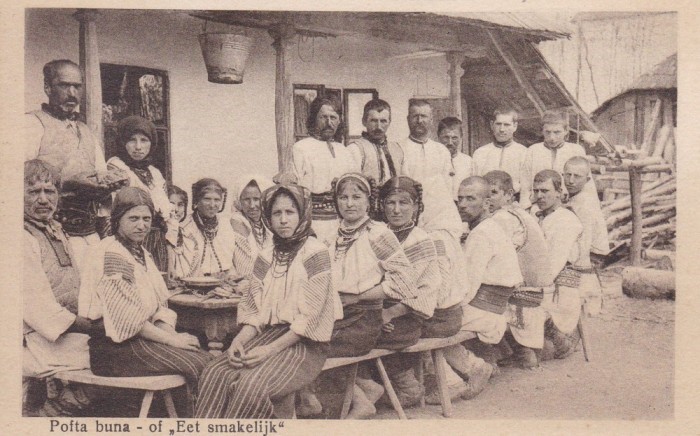

The fundamental theory of this movement is defined as “Forms Without Substance”, in which “Junimea” held the belief that the occidentalization of the Romanian cultural life was superficial and, therefore, doomed to fail. To the adepts of this movement, evolution had to be organic and occidentalization had to be done in a way that was adapted to the respective country. As a result, Romania in the contemporary period was nothing more than an impostor donning the cloak of modernism without truly evolving. To add to this, “Junimea” argued against the excessively agricultural economy of the country, citing that the labor of the farmer supported a frivolous “intellectual” system that was, definitively, unfruitful and did not aid the evolution of the country at all. They identified the lack of a bourgeoisie in Romania and spoke out against the excessively patriarchal nature of all aspects of day-to-day life.

Above all, “Junimea” believed in telling the truth about the situation at hand and, as a result, held the critical spirit to a high standard. They frowned upon mediocrity, formalism, and grandiloquence, and criticized the contemporary claim that the Romanian people were pure-blooded Roman descendants. Shunning false nationalism, form without substance, “Junimea” was also critical of the actions and beliefs of the “pașoptiști” (Forty-Eighters) which spearheaded the 1848 Romanian revolution, holding the belief that writing a piece of work just to have it written is fundamentally flawed, and that everything ought to go through a critical filter, ought to demonstrate its value first. They also argued that the former had struggled to piece together a nation without going through the essential, time-consuming stages of doing so. In terms of political beliefs, “Junimea” was a staunch opponent of socialism, on the grounds that Romania could not possibly adopt such a regime seeing as there was no actual proletariat in the country (due to the pre-1907 dependency on land leased from boyars).

Similarly, because “Junimea” identified only two classes in Romanian society- the peasants and the landowners (boyars), the existence of a liberal party was futile in itself. Apart from politics, members of “Junimea”, prominently Titu Maiorescu, were in favor of intellectual reforms that manifest themselves to this day- including favor of a phonetic alphabet over a Cyrillic alphabet, in the condition in which the latter was still quite popular in Moldavia. No doubt, the “Junimea” movement produced some of the greatest minds of Romania’s intellectual history- minds such as Mihai Eminescu, Ion Luca Caragiale, and did leave behind an important cultural legacy that impacts the approach to socio-cultural situations to this day, and raises the question of the relevance of their beliefs in a post-1989 Romania.

In “România, țară de frontieră a Europei”, historian Lucian Boia addresses this question. The theory of “forms without substance” as was endorsed by “Junimea”, is very much applicable in a country that, very rapidly, underwent a process of intense occidentalization following the death of a brutal Communist dictatorship. However, these ideas are, from some points of view, very extreme, seeing as, due to the geopolitical factors that existed in the time of the “Junimea” movement, increased occidental influence would have been inevitable. Now, perhaps the aforementioned theory is a viable perspective that can be applied to our present reality, and maybe it is what our country needs. But what I find that is lacking in this philosophy is that it is nothing more than an idea. An idea with veritable merit, indeed, but unless it is actually applied, unless it is regarded as a lesson, it will never be more than an idea in the present times and its truth, in this case, will lose its importance.

References

Boia, L. (2016). Romania, tara de frontiera a Europei. Bucuresti: Editura Humanitas.

Calinescu, G. (1983). Istoria literaturii romane. Compendiu. Editura Minerva.

Djuvara, N., & Anton, C. (2014). O scurta istorie ilustrata a romanilor. Bucureşti: Editura Humanitas.

Lupsor, A. (n.d.). Junimea, punct de cotitura in evolutia societatii romanesti. Retrieved from Historia website: https://www.historia.ro/sectiune/actualitate/articol/junimea-punct-de-cotitura-in-evolutia-societatii-romanesti

Manolescu, N. (2008). Istoria critica a literaturii romane. Pitesti: Editura Paralela 45.