by Georgia Mirica

It seems that the youth are always discontent with the world they live in, the world created by their predecessors, creating a perpetual cycle that manifests itself in the present as well as in the past. One of the best-known examples of this in Romanian history can be found in the “Junimea” literary and cultural movement that, in its time, put forth some theories that may be relevant to this day.

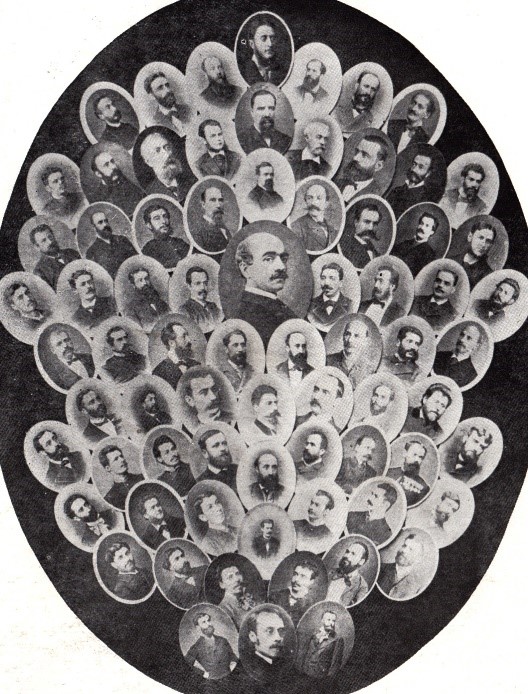

“Junimea” is the name of a literary and cultural movement (that can roughly be translated to “the Youth Movement”. This movement has its roots in the city of Iași, in the year 1863. More than just a movement, “Junimea” was an association that fostered the grouping of eminent intellectuals. Due to this fact, the value of this movement is partly constituted by its subsequent incompatibility with the term “historical construction”. Rather than a category created by philologists and literary historians with the purpose of sorting similar works into a group, “Junimea” represented the intentional creation of a literary and cultural movement in which the distinct characteristics of works produced by its adepts serviced the promotion of the aforementioned association’s ideas and philosophy. “Junimea”, although its creation was a contemporary of the foundation of the Romanian Academy, was not founded on a legal, contractual basis, and, instead, was viewed more often as a community as opposed to a strictly-structured society. As a result, the associative community was defined by the common perceptions of its members regarding politics, sociology, and culture.

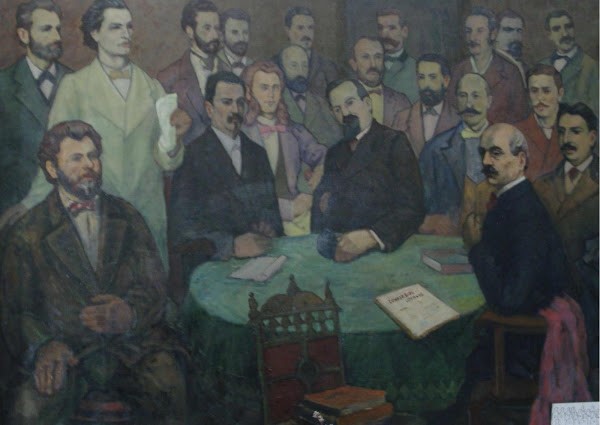

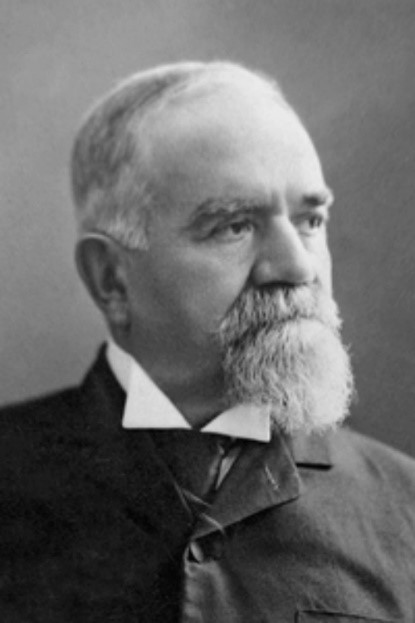

This movement manifested itself in two distinct branches- a literary cenaculum, in which its members assembled to discuss various pertinent topics, and a periodical newspaper entitled “Convorbiri literare” (“Literary Conversations”) that sought to promote the theories devised and works published by its members. The founders and initial members of “Junimea” were individuals from distinguished backgrounds, who had completed their studies abroad in Germanic countries, known today as future prime-ministers Titu Maiorescu, Petre Carp, and Theodor Rosetti, and poets Iacob Negruzzi and Vasile Pogor. The main activity of the associative community consisted of meetings under the prominent leadership of Titu Maiorescu and long discussions usually praising the critical spirit.

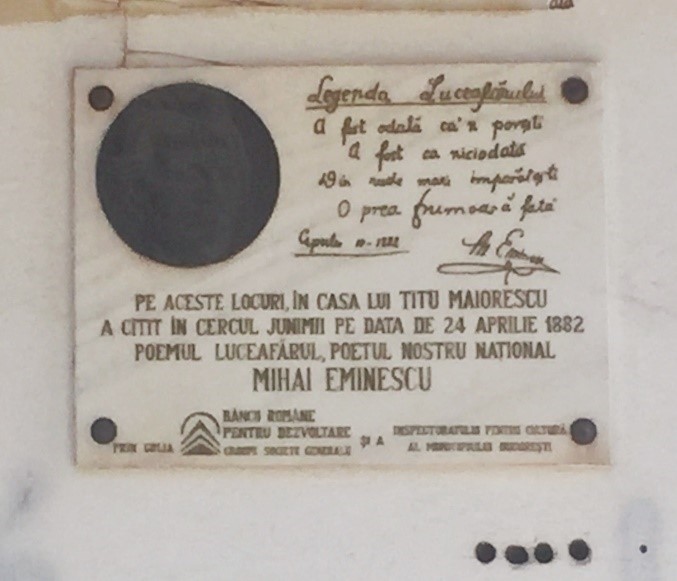

The “Junimea” movement’s timeline can be split into three definitive periods. Between the years 1863 and 1874, the movement’s foundations were laid in Iași and the movement quickly accumulated prestige through the association of figures such as Vasile Alecsandri and Mihai Eminescu. The next period is regarded as the culmination of the movement, spanning from 1874 to 1885, it represents the transition and popularization of the movement in the capital city, Bucharest (due to Titu Maiorescu’s appointment as Minister of Education). In this period, the majority of the movement’s members published what are presently regarded as their masterpieces, and presented them to the community. The year 1882 saw, for instance, the first recital of Mihai Eminescu’s “Luceafărul” in one of the regularly held literary cenacula. After this period, the movement slowly died out, falling subject to divisive political views and alienation from its initial philosophy. Due, in part, to the support of Petre Carp and other members of the Central Powers during the First World War and the clash with the anti-Austrian sentiment of politicians at the time, “Junimea” came to an end in 1916.

I would like to take this chance to apologize for the dryness of the text above. It is, in my opinion, the perfect example of an essential superficial, essential because it is intentional, intentional because it is nothing more than a diving board into the true essence of this movement and its larger significance.

References

Boia, L. (2016). Romania, tara de frontiera a Europei. Bucuresti: Editura Humanitas.

Calinescu, G. (1983). Istoria literaturii romane. Compendiu. Editura Minerva.

Djuvara, N., & Anton, C. (2014). O scurta istorie ilustrata a romanilor. Bucureşti: Editura Humanitas.

Lupsor, A. (n.d.). Junimea, punct de cotitura in evolutia societatii romanesti. Retrieved from Historia website: https://www.historia.ro/sectiune/actualitate/articol/junimea-punct-de-cotitura-in-evolutia-societatii-romanesti

Manolescu, N. (2008). Istoria critica a literaturii romane. Pitesti: Editura Paralela 45.